When I was 17, two things occurred which changed my life forever.

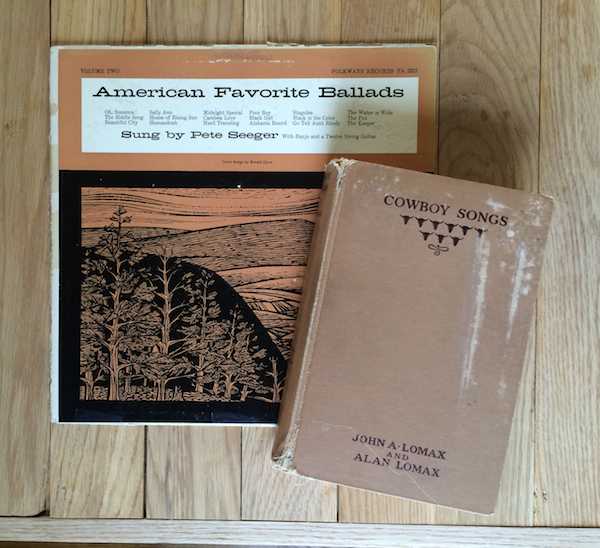

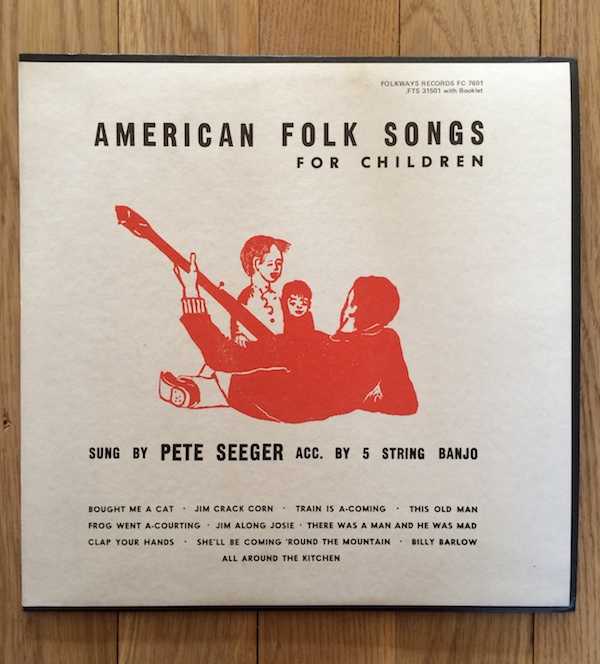

My grandfather passed away and left me a book by John Lomax entitled, Cowboy Songs, and I discovered Pete Seeger’s seminal “American Favorite Ballads” record series produced by Smithsonian Folkways.

Growing up as a ranch-hand in Silver City, New Mexico, the “real” history of the American cowboy was always important to my grandfather, and Cowboy Songs was one of the only genuinely untainted collections of that oral tradition with lyrical content that wasn’t screened or edited by its publishers to be “safe.”

As a musician wanting to know more about my personal heritage in American folk music, I soon inevitably discovered the work of Pete Seeger. With access to his live and candid albums made for Folkways, and his early traditional hits with The Weavers, these songs that had only existed on the pages of the folk anthologies I was reading actually came to life.

With Seeger maintaining a simplicity, passion, and voice akin to a spirit of as if he sang out a traditional ballad on the day it was written, I began to internalize the fact that everything I had been taught about engaging, appreciating, learning from, and making music was derived through a very different system not much older than my grandfather.

I began to see that great music didn’t have to be made by just coming up with “material” for live and recorded performances, but there was a much deeper root of common song that had been occurring naturally, and changing regionally as long as the human race has existed.

This was music birthed out of need for sharing common ideas or struggles, popular or unpopular, disposed to the circumstances of the writer’s family, community, national identity, or lack thereof.

The term “folk music” seemed like it had been culturally hijacked from me and interpreted for me as a commercial genre coupled to recordings based on the sound of a pretty acoustic guitar and a soft voice.

Essentially what I saw through Pete was the not-so-long-dead antithesis of music made as a means of the expansion of personal fame and empire, being that he’d say “I feel that my whole life is a contribution,” not just a sound, feeling, or recorded product.

Music could actually become a wonderful vehicle to bring people together and build the spirit and depth of their community—not only inspire the listening individual, as I had been so accustomed to.

Becoming more familiar with Pete’s work, I initially assumed he had long passed on as his contemporaries Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston, and Lead Belly had done decades before. In discovering that he was very much alive and active, as one working musician to another, I quickly wrote him a letter with a head full of questions concerning direction on initiating community-oriented music in an entirely post-indigenous city.

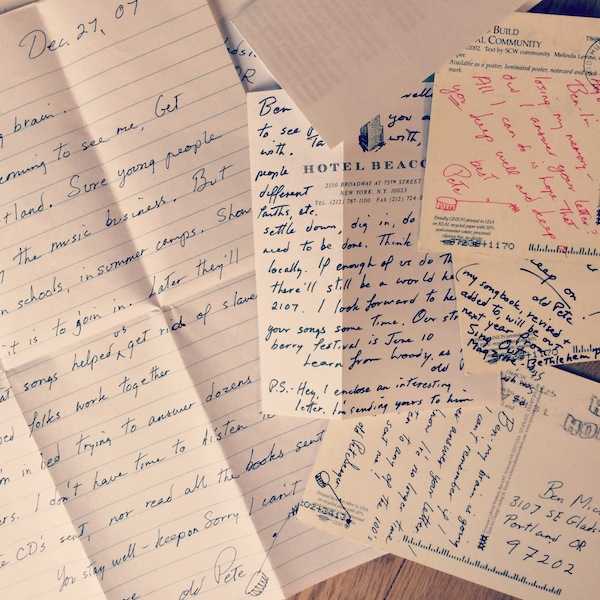

Not expecting anything in return, I was surprised to find a simple postcard in the mail with just a couple sentences of thanks and that he was “a lucky old guy to receive a letter like” mine.

Maybe it was youthful ignorance of the fact that he was a busy man, but I wasn’t satisfied with a simple reply so I kept writing with similar questions, and the responses grew from a sentence or two to a couple paragraphs with each exchange.

He continued to do his best to summarize solutions for my concerns with a couple nuggets of wisdom at a time, and a pointer to helpful individuals and resources.

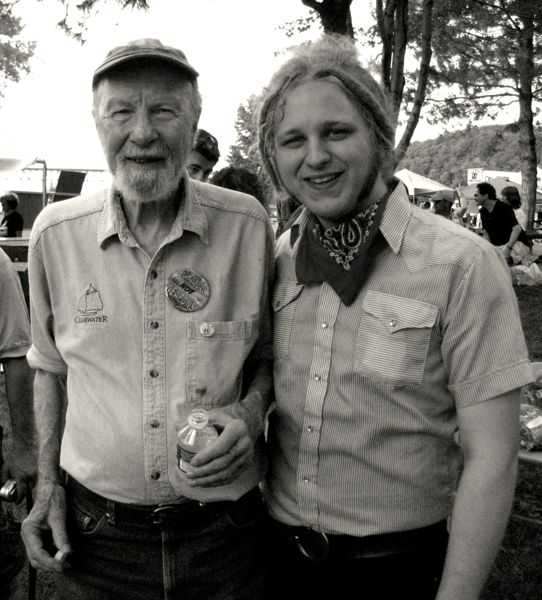

Eventually, I ended up receiving an invite to come out and join in the music at the annual Beacon Strawberry Festival near his home in upstate New York which Pete and his family had supported for years.

The indelible lessons I acquired in tracking his work from the time of our first correspondence, to spending a week of music and conversation with him and his family in Beacon, are thus:

The commercial industry does not have to define the way you do things. You have to define how to do what you know is best by changing the system you live in daily, a step (or song) at a time.

If you listen to any of Seeger’s live recordings, you won’t be able to go more than five seconds without realizing that most of what he’s trying to do is simply get people to sing together.

If you listen just a little more, you begin to realize that he’s also effectively making historic tunes relevant to the environment he’s in.

PBS aptly titled their 2008 biographical documentary, The Power of Song, essentially encompassing the philosophy of his work. It could easily have been called “The Power of Pete,” or “The Power of Folk” or something individually focused, but it becomes relatively hard to interpret his work that way when he’d constantly quote individuals like Aunt Molly Jackson.

Jackson was a miner’s widow from Clay County, Kentucky whose songs written from her painfully home grown experience helped fuel the founding of the National Miner’s Union, making a clean break from living under the continually deadly circumstances their former employers had provided.

Under his title chapter “What can a song do?” from his autobiography The Incompleat Folksinger, Pete recalled her passion about the matter, saying “Protest songs? Even the singer of dirty songs is protesting sanctimoniousness. … Propaganda or proper goose; the truth is what matters.”

To someone living in the era before the commercialization of music, who’d seen common songs change the entire way of life for her community, the fact that songs have meaning and can actually do something (no matter what label they’re given) was as real as the fact that she could talk about it. The label must’ve seemed like an inconsequential stereotype of her passion for doing something good.

Truly, recording technology is what changed music forever.

By the time that Pete hit the pop-charts with The Weavers in 1950 with a song like “Goodnight Irene,” the task he had taken before him was to broaden the spectrum of the topical song for the American public to know that they could engage with real, life-changing topics besides the only one that was safe (mostly) in all its various forms: love.

As their follow-up best-seller, “Tzena, Tzena” became another unlikely release during the American post-war era, bringing to light the fact that fantastic music and culture was happening around the world, not just in the very powerful USA.

Pop-music by this time was on a fast train away from producing urban hymns that meant more to families and individuals than the one who performed them, building up an immensely viable market through the perfect image of crooning singers like Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra.

Yet what made the market even exist goes back to one point in history, the proliferation of the Victor Talking Machine Company’s “Victrola” record player. With it, two completely new doors opened for the public: the ability to listen to anything without having to go anywhere or engage anyone, and the ability to be sold ‘music’ as a commercial product in the form of a medium other than a human performing it directly.

This literally marked the beginning of the end for the indigenous oral-traditions of the western world, drawing a hard line between the old and new era, and Pete knew it.

When one comes to the conclusion that there’s something they can see that they feel others aren’t able to and should know about, they can do one of two things: get pridefully cynical about their “enlightenment,” building up unnecessary animosity for themself, or bring a helpful idea to the table in a relevantly relatable way so that the community can grow and learn from it.

“Don't Play,” followed by a radio station manager’s signature. A leftover from the Weaver’s blacklisting during the McCarthy era.

Though not methodically compromising a core-conviction of enabling communities through bringing back their old songs and standardizing new ones, Pete chose to tie himself to the commercial industry knowing that there was something he could do: not to attempt to undermine it himself with useless rhetorical attacks, but to thoroughly organize with others like him to be a clear example of how much life can be found in the old alternative.

The simplicity of getting people of all religions, creeds, and associations together in the same room singing something they all relate to and/or believe in could be much more exciting than a hall packed with faceless individuals quietly focused on a person-centric performance.

Even when I met him, Pete hated having himself as a central focus, always redirecting conversations to the great work the community was doing together.

A neighbor of his from Beacon told me, “The best way to get to know Pete is to work along side him doing something useful, like picking up trash.”

No matter what form it took, contributing to something community-centric was his way of “turning over the temple tables” that be, if you will.

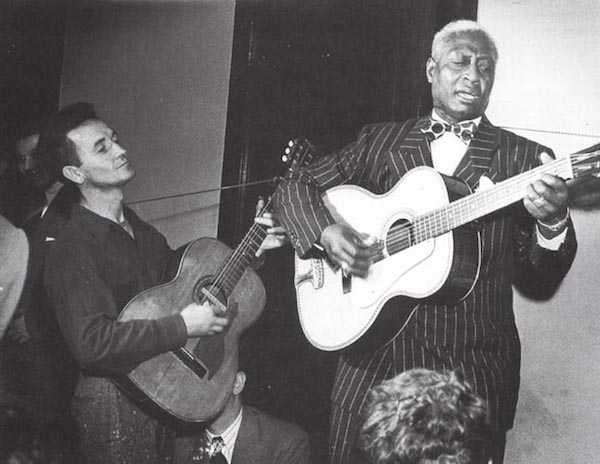

As a younger man in an age where members versed in the way people’s music used to be grew old, Pete was able to maintain direct access to quite a few of America’s surviving known and unknown members of folk music history before recording existed—many of whose songs (or arrangements) made it into our national archives at the Library of Congress, and the priceless anthologies collected first hand by John and Alan Lomax, Carl Sandburg, and William Doerflinger, among others.

This culture of preservation fell into two camps: publisher, and performer. You could read all you wanted to about the way songs used to be sung and what they meant, or you kept on where the songwriters left off by doing it yourself.

Songsters like Woody Guthrie and Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter became Pete’s counterparts in showing the world that folk music, in the truest sense of the word, was still very much alive and at work apart from the ever expanding recording industry.

From small town juke joints to Carnegie Hall they played for all audiences, turning performances into opportunities to get people singing together, and familiar with songs important to either their heritage or collective identity.

With blazing a trail for others to think critically via music and personally do something for the growth of their local human experience, this legacy becomes a critical idea to wrestle with at some point for contemporary musicians of 2014, during our post culturally-homogenized, global era.

In contrast, the results from our more popularly prominent school of music have facilitated patterns that appear to have benefitted not only a self-centric mentality, but have completely redesigned the conventions of music interaction on an individual and communal level. This is why…

Being a Rock-Star is bullshit. If your work doesn’t tackle the concerns of anyone more than yourself, it’s not worth your time. Building community isn’t glamorous, but the rewards are better than fame.

The creation of music as content for individual consumption is really only an entertainment ecosystem that has existed for arguably less than a century, resulting in an economy of hedonistic escapism, so far as to say: as long as the product has just enough broad-spectrum emotional familiarity, multitudes will buy it or be satisfied with it, as the bar for creativity and critical thought in music is continually lowered to what may be tolerable.

With such great emotionalism produced at such a rapid rate, this makes way for individually-targeted ‘microwaved’ empathetic experiences without a much deeper purpose than to feel something, rather than encouraging communally involved ones with a common cause.

This continually reoccurring process becomes naturally sustainable in the common exhibition of what I call the “headphone-lifestyle.”

There is no greater self-contained experience than one only available to the body of a listening individual. If one is subjected to be familiar only with sound rather than an individual artist making music, they are destined to remove the human element from the sound’s creation and associate it with either an idea, emotion, or memory.

Interaction with others becomes interaction with an extension of self, which can be beneficial with many other tools, yet is dangerous to the identity of music itself.

Instead this curates a reversal of shared-interaction: when said individual buys a ticket to see a show from the band that they had been individually listening to, and either silently watches, or is lost in an excitedly loud myriad of people.

Ultimately, this may show them that they are not as important as the ones exalted on the stage. It cannot only become an unhealthy manifestation of worshipping the idealization of what a rock-star is portrayed in image to be, but an intentional or unintentional dismissal of their worth in an associated “scene,” thus driving many to vie for acceptance within an imaginary demographic much “cooler” than the one they come from.

To clarify, there is a tremendous difference between this model and making the inspiring creative work of talented groups and individuals available to everyone, but what can be challenged here is our popular recording industry’s facilitation of a fantastically cool image, creating an unachievable fantasy for the common individual to acquire, who then may vicariously live it out through the products and services the industry provides.

If those products and services are accepted by a majority, then a purposed cultural-homogenization can be achieved. How did we get here? Circumstances and clever marketing.

By the 1960s, recording methodology reached a creative apex in available technology and artist ingenuity that will never again be repeated in this way and has been only emulated since (whether by use or building of instrumentation).

The market was ready to produce its Elvis, The Beatles, and Bob Dylan. Each of whom’s story is different, and whose musical contribution within the industry and to the public was huge, of course, but whose total glorification has left us generationally found wanting.

It’s done two things.

One, provided us with what I call Recursive Photocopy Theory (RPT), which is a core method of post-modern music crafting: with every proceeding generation of pop-musician copying and pasting past elements of earlier pop-music production for further use, the overall integrity of the end result becomes a degraded image of something before it. Just like a photocopy of a photocopy.

And two, artists feel culturally pressured to build a viable personal image, more so even than to grow in compositional ability and discovery, to maintain a hopeful relevance in letting others continually think they’re a “big deal” within the forefront of current or new trends.

This then perpetuates a “hit-it-big” mentality, eventually burning artists out by their late 20s when they never become commercially popular, yet the opportunity to do something communally relevant with their talents exists as long as they do.

The ever increasing need for the alternative to be resurrected (ironically at Pete’s death) is now more important than ever, if not only to have an alternative to fitting into total cultural-homogeny.

Pete really hit it right with his simple phrase he repeated to me and many others throughout the past few decades, “Think globally, act locally.”

Building small, globally minded, intentional communities that are individually authentic, but equipped to interact with any other one around the world seems to far exceed a lack of resistance to assimilation into an esoteric monster of one globalized society, making way for some universal “elite.”

Pete was able to jump into the process of global music-commercialization during his time in this way, organically growing another path culturally and environmentally with the door to access it from the inside-out. His collective work was done only with the help of willing communities, small and large, across the US (and the world).

This proves to be a reminder that: though wonderful to most of our senses, music itself isn’t as important as what you do with it. The artist has no idea of the repercussions of their work, but it’s very healthy to stay mindful that it can easily ripple a global influence, positive or negative.

This draws us back to an attempt at making a solid definition about something generally believed to be utterly subjective.

Pete said, “A good song reminds us of what we’re fighting for.”

Tackling community issues in song is at the heart of traditional folk-music, and has become a relatively lost art, or has been generated from RPT so that it topically contains a deluge of emotional struggle with no physically or historically concrete subject matter.

Those who make statements with their new or rearranged traditional lyricism are generally pushed to the fringes of relevant culture like languages that die. When English became the first language of the U.K., Welsh and its dialects were pushed to the edges of the islands, and now exist nearly entirely as a showpiece for historic reminiscence, sung at genre-specific events or recited in special-interest groups.

It would be ludicrous to say that folk music is the only music that serves a legitimate purpose, as one can draw incredible inspiration from the unending variety of forms music composition itself has acquired at this point, but unless it’s profitable, our culturally-uniform music industry is pushing critical ideas and purposes out to the point of total sterilization.

At the present time, our youth are either not aware of the power available to them in the methods behind making folk-music, or they seem to have to do their best to match up to producing something universally relevant by rooting themselves in trending commercial methods.

What did Seeger think? Well, he’d say: “Participation – that’s what’s gonna save the human race.”

No matter what you believe about that statement, I can’t forget about what stemmed from this belief in another thing he taught me: Never refuse an audience; always get them singing together no matter who they are.

In Pete’s words, he said “I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers, and I am proud that I have never refused to sing for anybody.”

With participation being one of the major themes of his work, he aptly summarized this entire concern to me in this way in one of our letters: “Sure young people are clobbered by the music business. But go to the kids in schools, in summer camps. Show ‘em what fun it is to join in. Later they’ll find out that songs helped us get rid of slavery, and work together!”

Without even saying it outright, he was able to encapsulate the fact that if a song is simple enough to bring children together and help them learn something while enjoying it, the performer is well on their way to giving that generation a better start than to only be subject to the industry’s influences.

In his autobiography, he also brought this up saying: “Singing with children in the schools has been the most rewarding experience of my life.”

To continue in on the spirit of this, if we collectively focused less of our attention on national shock-value entertainment, and more on songs and stories of community identity, we could turn our music into something that actually equips, not distracts our youth.

Singing to kids in school for free is nice, but how then is one supposed to make a living at music? You don’t—not directly.

Unless the opportunity clearly presents itself, living in an all-or-nothing mentality typically becomes a drain on the artist’s sanity, and the pockets of others they depend on unless they go to work to support themselves. Pete iterated this thought recalling he was told “that someone once asked Doc Watson for advice on whether or not he should become a professional singer of folk songs. Doc was reported to have answered in his usual grave way: ‘Do it as a last resort, when you’ve failed in every other way to make a living.’”

If you don’t know about Doc, the first thing to note is that being blind didn’t stop his commercial success which began in his 40s, and he was just as similarly interested in being an auto-mechanic as a musician.

Similarly, music is not the only good thing in the world, and not everyone is naturally disposed to make it. The place of importance that music itself is often lifted to culturally can also cheat the progress of other important working talents that artists possess that can benefit the growth of their community.

In Pete’s case, he quickly moved from organizing music performance and publication, to organizing political and environmental rallies, with one of his best known successful contributions being the effort to clean up the Hudson River, which had slowly become an industrial sewer that passed right by his home. In fact, the first conversation that he and I had in person was about water chestnuts that were native to the Hudson, and had begun to flourish again.

The way things were, doesn’t have to be better than the way things are. Knowing the past well can really help you change the course of what you don’t like about where we’re headed.

The world has changed a bit since Pete and Doc were in their prime.

How is it possible to maintain an honest approach to giving authentic folk-music in a new era that seems to have moved on entirely?

Just as Pete and others thoroughly held integrity during an earlier iteration of the recording industry’s expansion, so can anyone of this age keep on before our cultural experience is almost entirely wrapped into endeavors that can change at an executive whim.

Fear is the general enemy of doing anything, and if we aren’t afraid of the powers that be or the way others respond to doing something “real” with our time, we might actually be able to fulfill some goals that involve them.

To say that the era of indigenous western music is over and that its methods have become irrelevant is a contemporarily logical thought, yet in essence is also the worst enemy of our oral tradition’s existence and survival. We are at the door to letting our story in music become either an optional parallel path, or one changed on the peak of a parabolic track.

Using our tools to create experiences that draw others communally together rather than to build isolated, yet entertained lives is a great problem before us now.

The general roots-informed approaches I’ve been witness to are polarized in either an attempt to mirror the exact recreation of folk musics of the early to mid-century modern eras, or produce work in a more polished singer-songwriter market which is viable to a commercial niche.

Though wonderfully talented and enjoyable artists are making meaningful music in both ways, the separation between the identity of our cultural folk idiom and its ability to adapt and change to the induction of relevant digital tools and the community-building opportunities within the Internet holds the key to finally let it breathe beyond the attraction of what it once was in simpler times.

To maintain natural growth and relevance, just as in the historic cultural evolution of the 20th century, our common expression must be willing to adopt new tools as desired, is necessary, and needed while fully utilizing the power of its traditional methods.

Our tragedy happens when identity is defined by image, rather than image being a relatively unimportant byproduct of executing the method.

Additionally, the means of execution are then wrapped up in a process of maintaining an image easily stereotyped to fit an existing commercial genre. Applicable influence to our growth can then be hindered by the fact that the tools we are using are so coupled to what others think we should look like, that exploring the use of new mediums in the folk idiom is met with grave opposition because folk music’s aesthetic is now forever cemented in time at it earliest interceptions of audio and film recording.

The opportunity of global cultural integration and building strong communities in the Internet is not an enemy to folk music–the dehumanization and dissolution of its powerful components for market viability in advertising is.

A second culture now parallels the importance of regional community expression: the global.

Both are important, and neither of which deserve to be completely left behind for the other. Though not yet fully realized, vital tools are being further developed daily for making the possibility of advancement in indigenous collaboration available within the Internet.

Direct browser-to-browser audio interfacing (WebRTC), and new possibilities of in-browser sound generation through audio-specific programming interfaces (web-audio APIs), among other tools, are pushing the roof off of constraints previously known against realtime collaborative music projects.

What I foresee being immediately necessary as a next step into our universally-accessible paradigm of common folk expression is the iterated development of an organic ecosystem that takes the form of an application with a gravely simple interface. In simpler terms: the GitHub method applied to collaborative music making.

It could be an in-browser digital audio workstation that allows for the open sourcing or private working of current recording projects, with an ability to browse and collaborate on any project listed as open, or available to take its current form and make something else with it by request to the original author.

Crucially simple UI example: Audacity. I've successfully taught this software in condensed form to multiple classes of gradeschoolers.

It could also take the form of demultiplexing various instrument and voice inputs from around the world, adjusted for latency via distance by physical location, and sent as one audio output for internationally live performances in one or many physical locations. The lack of available synthesized instruments and sound generation there within would only be as limited as our time and creativity in making them.

As constraints are continually lifted, and further problems are solved, the possibilities in collaboration and creation are only as limited as our imagination.

I feel the repercussions of making incredibly simple tools like this easily available to everyone would have the possibility of bridging many socio-economic gaps in music making which have been previously unchangeable.

In the voice of Pete, “Any darn fool can make something complex; it takes a genius to make something simple.” This will only work if it’s simple enough, and not sacrificed to the current gods of advertising.

While introducing the old spiritual “You Gotta Walk That Lonesome Valley” at a Carnegie Hall concert with Arlo Guthrie in the mid 70s, Pete summarized the reality of ingenuity in folk music by repeating Woody Guthrie’s take on the matter: “One of the most important things which Woody taught me and a lot of others is that: you can make a combination between the best of the old and the new. It doesn’t have to be either one or the other, you can mix ‘em up!”

I would dare to say that this sentiment can be applied not only to communally forged lyricism and balladry, but to the mediums and methods of our shared expression in this era and beyond. As the web enables accessible community-oriented environments, and what once was musical hardware is continually fully emulated in the browser, the accessibility of creative interaction is as simple as having access to a computer with a modern browser installed, and the Internet.

I cannot say that this approach applies to indigenous communities outside of commercialized Western civilization who do not need it, but the creation within could lead to a new renaissance of tools, interaction, and the sound of our common song itself. This of course will look very different than regional old-world music, but the path is clearing to move forward in working within what we have rather than only by what we’ve seen in old films and recordings of the last century, taking much needed influence from those before us, but using their lessons to empower the critical growth of where we’re headed.

Dealing with similarly expansive changes in his time, Pete dealt with the tension of the artist staying traditionally informed, yet still inventive and good at what they do by relating this idea to one of his greatest influences, Lead Belly: “Nowadays when the artist becomes a virtuoso, there is a greater tendency to cease being ‘folk.’”

“When Lead Belly rearranged a folk melody he had come across—he often did—he did it in line with his own great folk traditions.” Pete draws the line here for us between the words “folk” and “authentic.” As we look to what can be done in the contemporary, holding fast to the understanding of where our authentic identity came from and what it is now, could in our own way, enable us to “turn the clock back to when people lived in small villages and took care of each other.”

The spirit of this truly has the chance to thrive in our physical and inter-networked world, or even within a collision of both. It’s become much easier to sacrifice our time and efforts doing something self-indulgent, but sacrificing our lives in building authentic community will continue to make our story one that grows into something greater than commercial artifice.

The recent passing of Pete Seeger concludes the swan song of an era in the American oral tradition that now almost entirely exists only in our written and recorded archives dedicated to such things.

We’re now physically left without that link to the way things were, and missing a direct conversation as to why people did such great things in a long line of their oral traditions and folk expressions.

Still, with the prolific gift of Pete’s body of work along with others like him, we’ve been given the great opportunity to preserve, foster, and build what the community music of our indigenous culture will look like in the era to come.

This doesn’t have to stop with the death of a folk champion, let’s do something together with our craft that matters now.